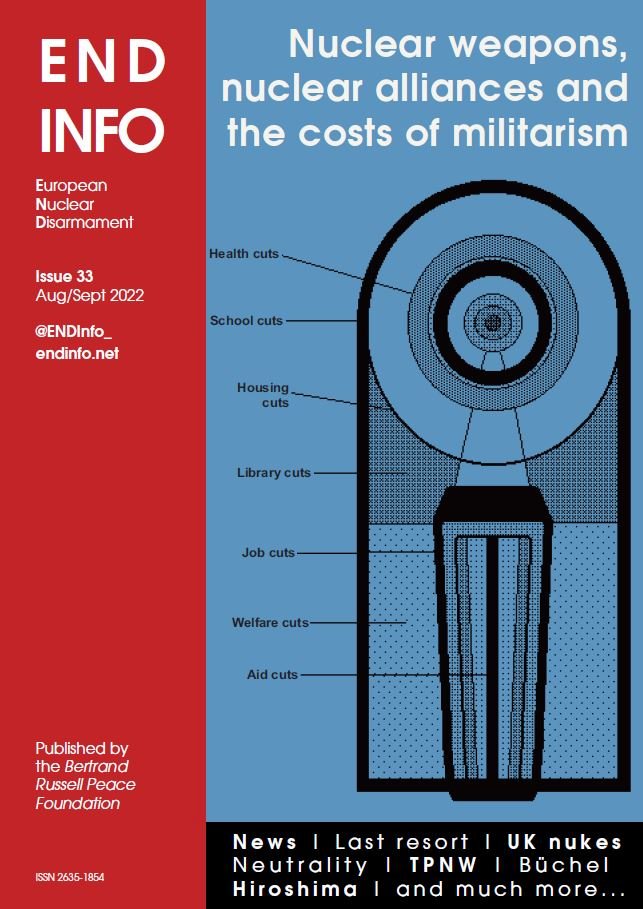

Nuclear weapons, nuclear alliances and the costs of militarism

Tom Unterrainer, Editorial comments

From END Info 33 DOWNLOAD

The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute estimates that in 2021, Russian military spending stood at $66,000,000,000 ($66 billion). In the same year the United States spent approximately $801bn. Over the same period, NATO member states, excluding the US, spent $363bn. As Simon Kuper pointed out in the Financial Times (9/10 July 2022): “If the US abandons Europe after 2024” - that is, if Trump or one of his protege’s wins the Presidential election that year - “other NATO states would outspend Russia more than sixfold.”

At the recent NATO conference in Madrid, Secretary-General Stoltenberg announced that the nuclear-armed alliance’s ‘high-readiness forces’ will increase in number from 40,000 to 300,000 by 2023. This is an almost eightfold increase and will include:

battlegroups in the eastern part of the alliance ... enhanced up to brigade levels, with forces pre-assigned to specific locations; and more heavy weapons, logistics and command-and control assets ... pre-positioned.

[Dr. Ian Davis, NATO Watch Briefing Paper No. 96]

In addition to the upgrade of units and material, President Biden has promised further troop and weapon deployments in Europe and a new HQ in Poland.

The content and implications of NATO’s new ‘Strategic Concept’ will be considered later but suffice to say that the global ambitions, spending commitments, reasserted role of nuclear weapons and the overall posture paint a deadly picture.

NATO is remilitarising and in so doing, enormous damage will be done to rational concepts of peace, security, investment, social security and the environment. Simon Kuper [ibid] quotes Dan Plesch of SOAS, University of London, on the implications of this new wave of militarisation. Plesch warns:

Worst case is we stumble into unintended global war. Best case is we stockpile and never use the weapons, but use our scarce resources on them.

Plesch’s warning of “unintended global war” should not be taken lightly and we should not forget what the dimensions of such a war would encompass: the risk of all-out nuclear war and the subsequent destruction of humanity.

In his opening comments to the much-delayed Review Conference of the Non-Proliferation Treaty, UN Secretary-General António Guterres warned that “humanity is just one misunderstanding, one miscalculation away from nuclear annihilation”. In subsequent comments, he explained that relying on “luck” - which has stood in the way of such annihilation on more than one occasion - is not a strategy for human survival.

The sharpening tensions arising from Putin’s invasion of Ukraine - including stark nuclear tensions - put us all at risk. Yet the response of NATO is unlikely to reduce the tensions, nuclear or otherwise. In fact, such responses follow a pattern we have seen in the past and will undoubtedly replicate the worst possible consequences.

Spend, spend, spend

The New York Times of December 8, 1987 reported that the sum total of United States missiles, aircraft and submarines capable of ‘delivering’ so-called ‘strategic’ nuclear warheads amounted to 11,786. The targets for these weapons were 220 urban industrial centres across the Soviet bloc. As Seymour Melman points out in The Demilitarized Society: “Hence, US forces have more than fifty times overkill capability.”

Melman notes that if this “overkill capability” was reduced by 75%, a budget saving of $54.6 billion ($142 billion in 2022) would be made. Such a reduction would have left the US with an “overkill capability” of twelve. The Demilitarized Society (1988) focuses on the problems arising from sustained and extreme levels of military spending in the post-WWII US economy. He explains that whilst money, skill and effort were poured into creating machines of mass annihilation:

The US now lacks a modern rail system, a modern highway system in good repair ... The city streets are poorly paved. Between a fifth to a third of the highway bridges in the US are rated as needing major repair. Decent housing is no longer available for millions. There is a growth of homelessness and hunger ... Important parts of the population draw water from aquifers that are contaminated. The national parks are in poor repair. The libraries are poorly operated. Waste disposal systems violate modern technical standards. The public school buildings of New York City require an expenditure of $8 billion for decent repair.

Between 2002 and 2016, the top 100 weapons manufacturers and ‘military service’ companies logged 38% growth in global sales. In 2016, these sales – excluding Chinese companies – amounted to $375 billion, turning $60 billion profit. Between 1998 and 2011, the Pentagon’s budget grew in real terms by 91% while defence industry profits quadrupled.

In the 1970s, investment in the ‘information technology’ sector stood at $17 billion. By 2017, investment in this sector exceeded $700 billion. In the same year, Apple’s market capitalisation stood at $730 billion, Google stood at $581 billion, and Microsoft stood at $497 billion. Meanwhile, Exxon Mobile – the highest placed ‘industrial’ company – had a market capitalisation of $344 billion. By comparison, the arms manufacturer Lockheed Martin had a capitalisation of around $321 billion and Rolls Royce $21 billion at the end of 2017.

Whilst the United States and other countries continue to purchase – and use – vast quantities of ‘conventional’ weaponry, the extraordinary figures quoted above occurred alongside the unleashing of a ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution’, powered by significant leaps in capability in computing, robotics, artificial intelligence, biotechnology, ‘autonomous’ vehicles and the rest. Ever greater sums are being spent on military and policing applications of the ‘fruits’ of this ‘Revolution’. So much so, that the sociologist William I. Robinson (Race and Class, 2018) identifies a trend towards what he terms ‘militarised accumulation’ as a ‘major source of state organised profit-making’.

In 1988, Melman warned that:

[M]assive, sustained military spending is, qualitatively, the single most critical factor in the cumulative depletion of the industrial economy. If this is dealt with decisively then the rest can be addressed. If that factor is unattended, then the rest is rendered unmanageable, and a process of continued decline is locked in place.

Such massive, and long-term, patterns of military expenditure and the material consequences on society at large are made, consistently, in the name of ‘security’. Each and every bullet, missile, nuclear warhead, bomber, armed drone, submarine, warship and tank is - we are told - there for ‘our security’. This militarised approach to ‘security’ is riddled with contradictions.

Militarised ‘security’

Climate change constitutes a serious threat to global security, an immediate risk to our national security and, make no mistake, it will impact how our military defends our country. And so we need to act - and we need to act now.

President Obama, May 2015

The US army is the most highly funded military organisation in human history. It is also the single largest institutional polluter on the planet. Obama’s eloquently delivered speeches on the risks associated with climate change morphed from initially wholesome appeals for action to save humanity, to framing the question as a matter of national security. As Nick Buxton points out (‘Securing whose future?’ The Spokesman 134):

The Pentagon is the world’s single largest organisational user of petroleum: one of its jets, the B-52 Stratocruiser, consumes roughly 3,334 gallons per hour, about as much fuel as the average driver uses in seven years.

As state level reaction to climate catastrophe incorporates more militarised ‘security’ responses and as multinational efforts at climate change reduction - such as the recent COP26 - fail to meet needs and expectations, it seems likely that militarised responses will be emphasised above other forms. After all, it is much easier to secure funding for military expenditure than for anything else and such expenditure drives corporate profiteering:

US defence contractor Raytheon openly proclaims its ‘expanded business opportunities’ arising from ‘security concerns and their possible consequences’, due to the ‘effects of climate change’ in the form of ‘storms, droughts, and floods’. (Buxton)

Neta Crawford from the ‘Costs of War Project’ at Brown University estimates that in 2017 alone, the US military emitted more carbon dioxide than Sweden, Denmark and Finland combined (Jessica Fort and Philipp Straub, ‘The Carbon Boot-Print’, The Spokesman 144). Freedom of Information Act (US) requests to the US Defense Logistics Agency, which is responsible for managing fuel purchase and distribution show that in 2017, the Department of Defense emitted 59 million metric tons of carbon dioxide and that from 2001 to 2017, a total of 1,212 million metric tons of the same gas was emitted. These figures include the period covering the bombing, invasion and occupation of Afghanistan and the illegal war against and occupation of Iraq.

Not only do wars, the preparations for war and militarised responses to ‘security’ risks have immediate destructive consequences in terms of death, depletion of resources and environmental damage: each and every day that sophisticated and expansive capabilites, such as those embodied in the US military, operate means additional releases of greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere. The impact of US and allied military operations in Iraq could be seen on the TV screen. Civilians on the streets of Baghdad and elsewhere saw the death and catastrophe first hand. What was not reported or broadcast and what has gone largely unmentioned is the legacy of environmental harm arising from these events.

How many B-52s flew in the years of war and occupation? How many hours in total were they in the air? How many gallons does that amount to? How many cubic tons of greenhouse gasses? How many more fractions of a degree did this take us to catastrophic temperature increases? What militarised responses have been put in place to ensure ‘security’ as a consequence of this increase in temperature? How many B-52s will it take to ensure ‘security’ from the consequences of war?...

This is just one example of the contradictions that arise in militarised responses to ‘security’. In common with other examples, it shares the features outlined earlier: the enormous sums of money devoted to military spending and the way in which such spending shapes the economy more generally. This example also shares another, connected, feature with other militarised responses to ‘security’: the fact that such responses simply make matters worse.

Law of the instrument

In his The Psychology of Science (1966), Abraham Maslow made the following observation:

I remember seeing an elaborate and complicated automatic washing machine for automobiles that did a beautiful job of washing them. But it could do only that, and everything else that got into its clutches was treated as if were an automobile to be washed. I suppose it is tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it were a nail.

Whatever else you might think of Maslow’s psychological theories, this observation - an outline of the ‘Law of the Instrument’ - seems a close fit to NATO’s approach to ‘security’. The nuclear-armed alliance is on the hunt for nails.

However, the fact that NATO is armed to the teeth with hammers is not a sufficient explanation for why it sees every problem as a nail. The purely military-industrial aspect of militarisation might indicate how NATO will react in any given circumstance but it does not account for the US-dominated, nuclear-armed alliance’s wider aims and perspectives.

The preface to the 2022 document explains:

The Strategic Concept emphasises that ensuring our national and collective resilience is critical to all our core tasks and underpins our efforts to safeguard our nations, societies and shared values ...

Our vision is clear: we want to live in a world where sovereignty, territorial integrity, human rights and international law are respected and where each country can choose its own path, free from aggression, coercion or subversion. We work with all who share these goals. We stand together, as Allies, to defend our freedom and contribute to a more peaceful world.

Fine sentiments. Yet the reality of NATO’s actions, historic and contemporary, and the belligerence of certain NATO members today, exposes these sentiments as insincere waffle. NATO’s new Strategic Concept actually reflects Jens Stoltenberg’s perception - and we should assume he largely acts to telegraph the views of the US, in particular - that “we now face an era of strategic competition”.

Whereas the 2010 Strategic Concept could proclaim that “the Euro-Atlantic area is at peace and the threat of a conventional attack against NATO territory is low”, the 2022 version warns: “the Euro-Atlantic area is not at peace ... We cannot discount the possibility of an attack against Allies.” Russia is “the most significant and direct threat to Allies’ security and to peace and stability in the Euro-Atlantic area”. China is a “systemic challenge” and China’s “stated ambitions and coercive policies challenge our interests and values.” Russian/Chinese relations are a “deepening strategic partnership”.

In the same way that President Bush Jnr concocted an ‘Axis of Evil’ to mobilise support for his wars of aggression, NATO has now outlined a new ‘Axis’ of threat, systematically aiming to link Russia and China. All the better for attempting to justify NATO’s tilt to China - some distance away from the North Atlantic area! In response, China’s mission to the European Union stated:

NATO’s so-called Strategic Concept, filled with cold war thinking and ideological bias, is maliciously attacking China. We firmly oppose it.

We previously argued that US foreign policy under the Trump administration reflected wild and reckless attempts to maintain US influence in a period of shift from unipolarity to multipolarity (‘Global Tinderbox’, The Spokesman 141). The ‘bonfire of treaties’, aggressive statements and Trump’s Nuclear Posture Review reflected these attempts. At the time, Trump could not take NATO with him and devoted some energy to attacking the nuclear-armed alliance, not least for member states reluctance to meet spending commitments.

Trump is no longer the US President, but NATO is now spending positively Trumpian amounts of money on armaments and rearmament. NATO has also fallen into line with US concerns about the emergence of alternative centres of power and influence. This is why they were happy to sign up to the new Strategic Concept and why ‘partners’ from Australia, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea were welcomed in Madrid.

A nuclear-armed alliance

The strategic nuclear forces of the Alliance, particularly those of the United States, are the supreme guarantee of the security of the Alliance ... NATO’s nuclear deterrence posture also relies on the United States’ nuclear weapons forward-deployed in Europe and the contributions of Allies concerned.

NATO 2022 Strategic Concept

If, for NATO, every problem is a nail, then the biggest hammer at its disposal is the nuclear weapon. As the Strategic Concept makes clear, it is the “supreme guarantee” of ‘security’. Only a truly sick mind could confuse a world-ending weapon of genocide withanything of the sort, but this is the reality we are dealing with.

The expansion of NATO’s nuclear bootprint across Europe (see END Info 32) and the steady incorporation of Australia, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea into NATO’s strategic thinking (see END Info 27 for analysis of AUKUS) are conceived of as ‘security measures’. These measures, along with massive increases in military spending and troop deployments, sow the seeds of potentially catastrophic outcomes. The catastrophe could be immanent, medium- or long-term, as risks multiply and as pressing concerns around climate change, hunger, pandemic and health intensify.

A truly secure future must mean working for peaceful outcomes to these challenges, not preparing for war.